Connect with us

Published

5 years agoon

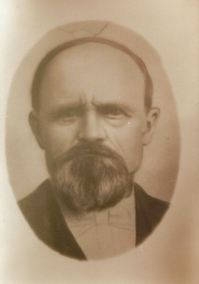

Very few people in today’s Lehi would recognize the name, Isaac Chilton. But 150 years ago, he was the “go-to” guy for the hardest jobs in the new city on the north shore of Utah Lake. Physical labor was simply the order of the day. Isaac Chilton needed to not only survive in the difficult pioneer era of Lehi, he wanted to thrive and did so because of his incredible strength, tenacity, endurance and unique skills.

He immigrated to the United States from the coal mines of Wales, where at the age of twenty-nine, he heard Mormon elders preach of a “restored gospel of Jesus Christ.” According to his journals, he told his wife Ann, “there is something important in what they say that rings true in my heart.” He attended a few meetings with Welsh saints, then became deathly ill with cholera. The Mormon elders came and pronounced a blessing “to heal him” and he arose from his bed “without a trace of the illness in my bones,” according to his journal. Chilton joined the Church, sold his home, bid his extended family goodbye, and boarded a ship cross to America.

Isaac Chilton was born in Monmouthshire, Wales December 7, 1830. He married Ann Watkins and had three daughters before converting to the new religion and immigrating to the U.S. on the ship “Underwrighter.” His family crossed the plains in 1860 with the William Budge wagon train. He worked hard enough in Florence, Nebraska to purchase a covered wagon, two oxen, a milk cow and food supplies. One of the oxen died en route and he put the milk cow in the yolk harness where she not only helped pull the cart onward to Utah but gave the little family milk and cream for the journey.

When they arrived in the Salt Lake Valley in October of 1860, Chilton and his family were escorted to Lehi the following day. Just two years later, his wife Ann and infant son died in childbirth. He was left a grieving father with three children. Bishop David Evans told him to go up to Salt Lake City and greet the next wagon train of Welsh converts and look for a young woman to help him with household chores. Two months after the loss of his wife and infant son, he was introduced to the David Pearce family. The Pearces were Welsh converts who had just arrived in Salt Lake. Chilton asked David Pearce if he could hire his daughter Elizabeth to perform household duties. David consented. The Pearce family also moved to Lehi where they were given a small log home by a departing citizen named William Snow, who had just been called to settle in Pine Valley, Utah, near St. George.

After seeing the “industry and love” Elizabeth quickly bestowed upon Chilton’s daughters and household, Isaac asked Elizabeth, age 23, to marry him. She consented and in 1863 they were married in the Endowment House in Salt Lake City.

Isaac had been a hard-working coal miner and was immediately asked to help dig a newly discovered silver mine for John Beck. Chilton soon helped with the development of one of the richest silver mine strikes in Utah history. He was never paid for his mining work but contracted with early settlers to dig wells. He was also hired to be a “wheat fanner.” His job was to use a large fan-shaped paddle which called for him to pump it up and down as wheat was shoveled from wagons into large wooden bins. The fan would separate the wheat kernels from the chaff. It was a hard job that few men could perform, but Isaac could “man the fan” for an incredible eight hours a day. His pay was rendered in wheat, and his family was “breaded up” for the Winter. In the evening, he began to help neighbors dig wells. His diminutive size and incredible strength and skill with a pick and shovel brought many calls for his expertise.

One hot summer day, a request came from Joseph Dorton, who had a Pony Express station west of Lehi. Dorton was a butcher by trade but thought his Pony Express Station had great potential as a stopover place for freighters, travelers, and immigrants headed West. Dorton had hauled water to the station in large barrels for two years before asking Isaac Chilton to dig him a well. Chilton took one look at the terrain and said, “I don’t think there is water here, but I will give it a try.” The process of digging a well consisted of using a shovel and pick to dig the hole as well as the critical skill of stabilizing the walls of the hole with either timber or rocks. Isaac used rocks because they were cheaper, and he knew how to bind them together with lime, water and sand.

He had dug several wells as deep as 30 feet for Lehi neighbors, but Joe offered to pay him $80 to go as deep as 50 feet. The dangers were obvious; the sides of the well could cave in at any time. The process called for him to dig the dirt and put it in a bucket that was hauled out by an assistant with a hand pulley after he descended below 8-10 feet and could no longer throw shovels full of dirt out of the hole. The “digger” also had to worry that a tool or rock may fall on his head and kill him.

Chilton had dug several Lehi wells but never gone deeper than 30 feet to hit clear, cold water. He had already dug nine wells in Lehi for friends and neighbors without pay. The word got out in Lehi that Isaac Chilton was digging a well for “Joe Butcher” (nickname) on the west side of the Jordan River. Farmers and land speculators began to gobble up as much property as possible near “Joe Butcher’s Well” (Pony Express Station). At 35 feet, Isaac had only found rocky dry soil and informed Joe that the hole was bad, and he was wasting his time. Joe pleaded with him to continue and gave him an advance of $40. Isaac took the money, dug down 20 more feet through more rocks and dirt before proclaiming it a “dry hole.” The attempt was abandoned in Chilton’s first unsuccessful well-digging effort.

Dorton ran the station another five years before leaving the venture and taking his labors back into Lehi proper. As a boy, my dad took me out to Joe Butcher’s well on two occasions in the 1950s. We were rabbit hunting. He told me the story as it had been told to him by his grandmother (Mary Elizabeth Chilton Fowler). All that remained of the site was a pile of dirt and a deep depression in the soil with another pile of rocks and scattered pieces of wood from the horse corral that had been abandoned 80 years earlier.

Chilton was also a noted law enforcement officer for nine years in Lehi along with his close friend, Thomas Fowler, the U.S. Marshall, and Lehi City Sheriff at the time. At the onset of the Blackhawk War, Lehi was asked to provide a police officer for the force of Indian Fighters. Two policemen volunteered, namely, Thomas Fowler and Isaac Chilton. They flipped a coin and, as Chilton recorded, “Fowler won and got to go fight.” Fowler and Chilton were bound together as family when Isaac and Elizabeth’s daughter Mary Elizabeth Chilton, married Thomas Fowler’s son, Edmund Henry Fowler.

Although Chilton’s first income and sustenance came from “fanning wheat,” he was also a successful farmer. In addition, he contracted to lay railroad ties/rail for the railroad company. He was industrious, well-liked, and held many Church leadership positions, including Branch President, Bishop and missionary. His second wife, Elizabeth Pearce Fowler, died at the age of 38, leaving him with eight children. She had given birth to five children and they had only been married 15 years. He later married Mary Jones and who also preceded him in death as did his fourth wife, Jane Jenkins. Isaac Chilton, who only stood 5’5″ died as a Pioneer giant in 1911 at the age of 80. His funeral was attended by hundreds of devout Lehi neighbors and friends. He is buried in the Lehi City Cemetery.