Arts & Culture

Spring runoff creates perfect storm and floods in 1983

Published

7 years agoon

Lehi came together to keep water where it belonged

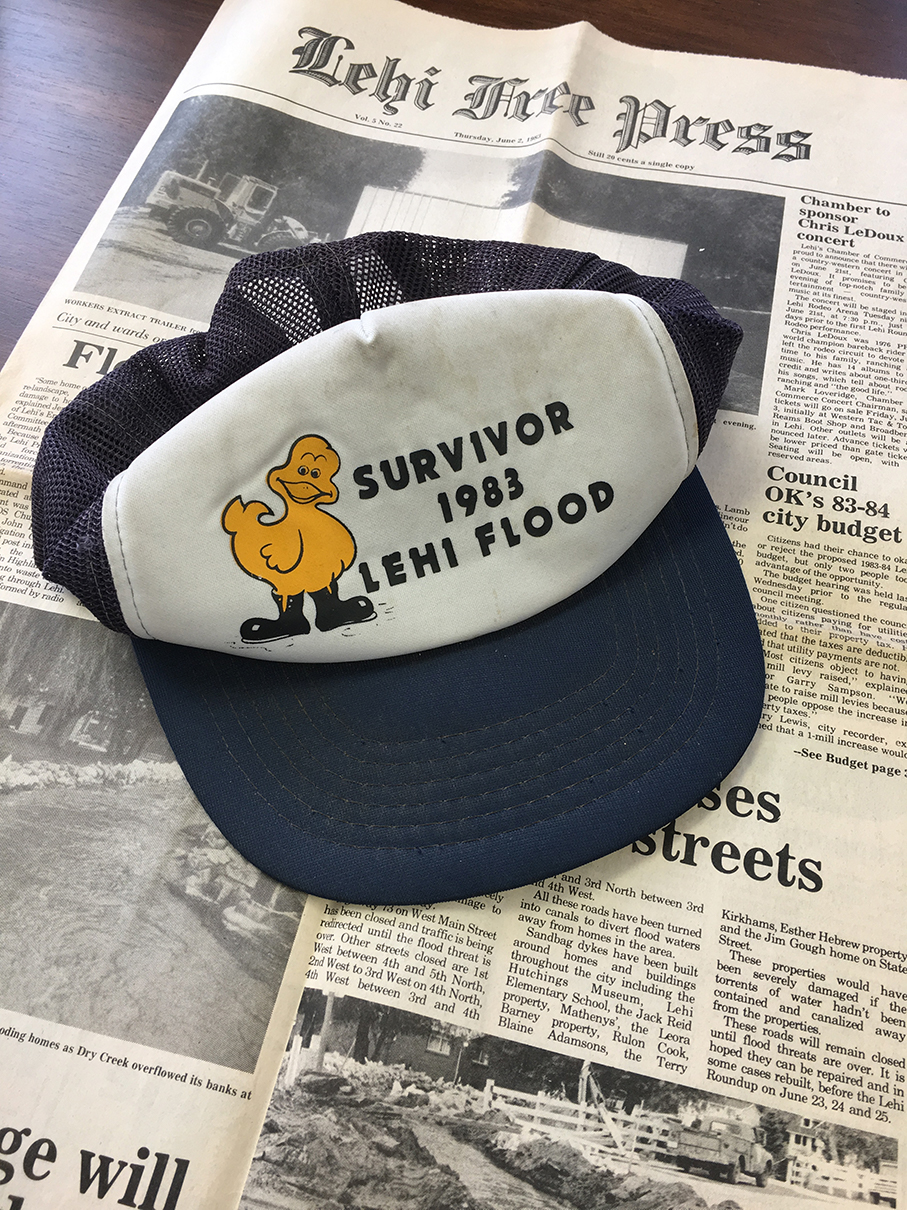

For those who lived it, the spring of 1983 will never be forgotten. Unlike this year, the city of Lehi faced unprecedented runoff. A combination of record snowfall, saturated grounds, warm rains, and temperatures in the 90s over Memorial Day weekend that year created the perfect convergence of events.

“I used to like to take my binoculars to Alpine and look at the mountains,” said Gary Lewis, the city recorder and financial officer for Lehi in 1983. “It was the only time in my life I could see waterfalls all over the mountain.” With each passing day, it was clear flooding was imminent.

The governor of Utah had even declared a state of emergency, but the federal government declined his plea for aid.

In anticipation of what seemed the inevitable, “Every waste ditch in Lehi was filled to the brim to keep the water moving,” said Russ Felt, bishop of the LDS 13th Ward at the time. “There was an enormous effort to keep the water where it belonged.”

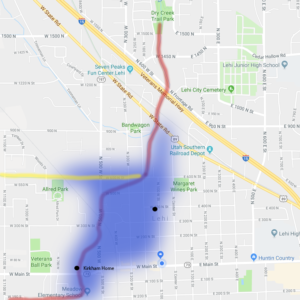

The waters that run off the mountains above Alpine flow through Highland and into Lehi by way of Dry Creek, which runs from the north, under State Street and into the culvert at Lehi Elementary. That culvert was always an issue, said Lewis, as it wasn’t big enough to accommodate excessive amounts of water. Therefore, high waters just flowed over it, flooding the school grounds and everything in its path.

Jim Smith, Lehi’s emergency coordinator, and Lewis worked together to coordinate the city’s efforts. “It was a tough situation,” said Lewis. “We had never been through anything like that. We were still a small city.”

“The LDS wards played a big role,” said Felt. “The city supplied the supplies, but the wards enlisted the help.”

Preparing for the Worst

On May 19, the call was put out for people to fill and place sandbags.

Over the course of the crisis, “Hundreds of people turned out,” said Lewis in awe, “literally hundreds.” Dirt from the sandpit by Airport Drive was brought to the Rodeo Grounds and other locations. From there, volunteers bagged and delivered it. “Everyone, men, women, teenagers, and hundreds not even from here came.”

“I remember one Sunday after taking the sacrament, our bishop told everyone to go home and change clothes and meet at the Rodeo Grounds to fill sandbags,” said Lehi native Lee Anderson.

Lewis’ wife Rhea remembered working with other women to make sandwiches for those filling sandbags. Everyone pitched in.

Members of the LDS 10th Ward were especially concerned about the conditions as its boundaries included the waste ditch as well as Dry Creek in the area of Lehi Elementary. Julian Mercer, head of the Emergency Preparedness Committee for the 10th Ward, wrote, “None of us had a clue about sandbagging. We weren’t sure what a sandbag looked like, how big it was or how full it should be.”

They soon learned that a filled plastic grain sack could easily weigh over 100 lbs., requiring more than one person to lift. A tightly packed 50-pound sandbag wasn’t malleable, but a loosely filled 40-pound bag was just right. One person could lift it, said Lewis, and it could be worked into any shape needed.

Just getting their hands on enough sandbags was a challenge in the beginning as they were expensive, and the LDS wards and stakes were hesitant to buy thousands. Eventually, the city provided the bags. But until then, Mercer wrote, “The purchase of sandbags by the individuals presented our first major problem, because those people wanted to use the bags for their own homes … the committee soon realized this could not be an individual effort, … we must work together to keep the water in the ditch, thus protecting everyone. The beehive concept soon came to fruition. The battle could not be fought from house to house, this would be an impossible task.”

On May 19, the community filled nearly 1,500 sandbags.

One of the homes expected to take a massive hit was the home of Dean and Gloria Kirkham at 708 West Main, just west of Harmony Hills Assisted Living today. With an irrigation ditch running behind their home, Dry Creek along its east side and the bridge over Main Street, under which Dry Creek runs, in front of their home, the family was thankful for all the help they could get.

“His whole ward filled sandbags for him,” said daughter, Becky Kirkham Beck. “It was so nice. The town really came together. There is nothing like a disaster to bring people together.”

When the Waters Came

It wasn’t until the early Sunday morning hours of May 29, that the high and rising waters did what everyone was dreading. The mountain had spent the day quenching in the sun’s rays, and the runoff, which took until the middle of the night to reach Lehi, was intense.

With or without permission from the city, Mercer said, Dave Turner and Jerry Beck, on their backhoes, worked with residents that night to take out bridges that they could see were going to cause major bottlenecks as water and debris made its way through Lehi. The bridge at 400 North and 200 West came out that night as well as a foot bridge, a bridge at 500 West and 500 North and the bridge in front of the Kirkham home on Main Street.

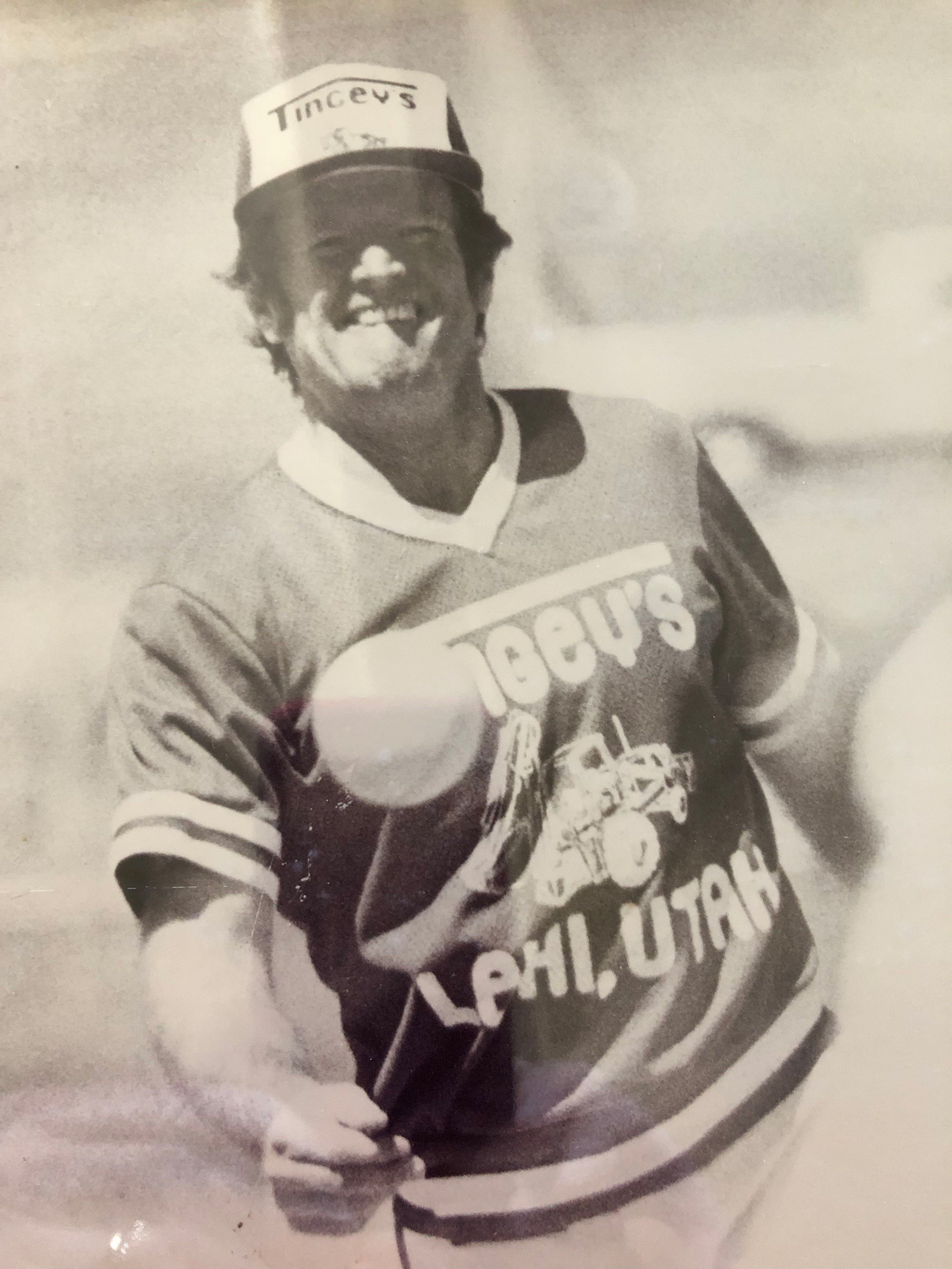

A 1983 Lehi Free Press article hailed Dave Turner a hero for using his backhoe in the weeks prior to the flood to stabilize his neighborhood when many did not feel it necessary. It says when the flood finally came on May 29, Turner worked 72 hours continuously. “For his work,” it reads, “the people of Lehi renamed Dry Creek to Turner Creek.”

In total, Lewis said six or seven bridges came out during the crisis. Fortunately, the sandbags that had been placed worked to protect the homes and guide the waters, turning streets into rivers and reducing residential damage.

“The water came up within three feet of their home,” said Beck of her parents’ home. They got water in the basement, but the home was not lost. “Of course, Daddy and my brother spent whole nights walking the creek, fixing the breaks in the [sandbag] dams so that the house wouldn’t flood.”

Felt had similar memories, “I spent whole nights with my son walking the creek to see where it needed to be shored up.”

Jen Hall, daughter of Blaine and Marie Adamson who lived at 500 North and 100 West and where a lot of sandbagging had taken place, recalled that the community’s efforts helped reduce the damage her childhood home sustained. Thankfully, she noted, the cinderblock walls of her home acted as a filter so the water that did get in was clean.

A Crazy Time That Brought Out the Best

While the streets of Lehi were being flooded, Utah Lake was also working toward its highest levels ever recorded.

Lehi native Judy Hansen recalled, “I remember driving on the back roads down by the lake, and there was water on both sides of the road. The little white house on the Saratoga Road bend was an island sitting in the water.”

“It was just so strange to have water from the lake lapping up on the road,” said Beck.

Felt remembered checking on, “Mrs. Brown,” a widow whose home sat southwest of town in an area that could have easily been compromised. When he and his son arrived to help, they discovered a young man who had worked for the woman’s husband who had already shored up her home with sandbags. “He had done an exceptional thing,” said Felt. “That’s good stuff.”

Although the actual crisis in Lehi lasted 10-12 days, Lewis said the impact was felt for months, if not years, because so many bridges had to be rebuilt.

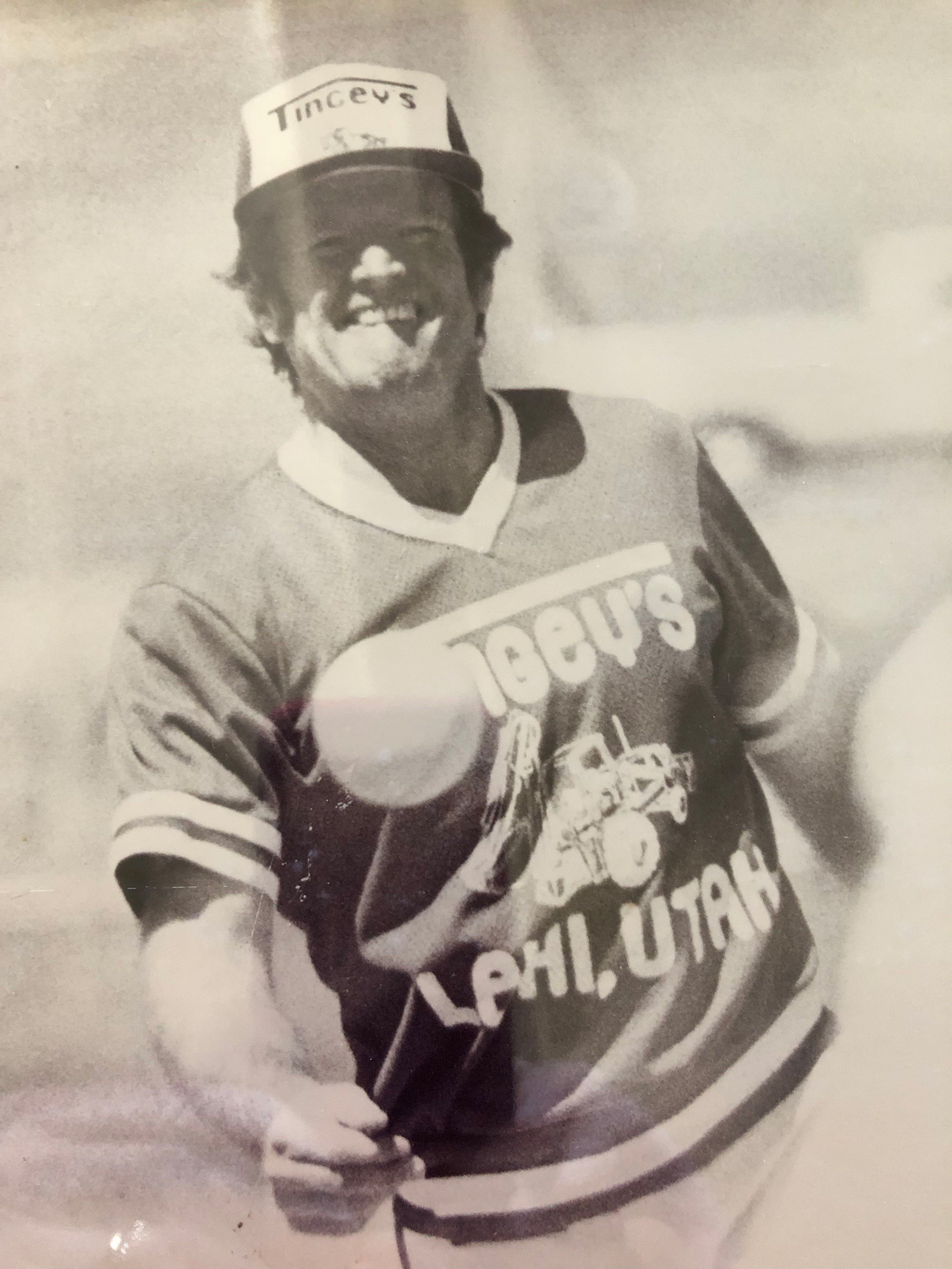

Members of the Dean Kirkham family observe the rising waters of Dry Creek which ran just east of their home at 708 West Main. The bridge over Main Street in front of their home had to be taken out during the course of the flood to minimize damage to their home and allow the ferocious runoff to travel freely to Utah Lake.

Lehi was not the only community affected by the moisture that year. The mountain town of Thistle, up Spanish Fork Canyon, was swallowed in a landslide, downtown Salt Lake City had streets turned into rivers much like Lehi’s and Farmington and Bountiful had their own devastating mud slides.

Then Utah Governor Scott Matheson was famously quoted for saying, “This is a hell of way to run a desert.”

Felt said, “It was quite a time. It really drew people together. Everyone came together to help take care of the water.”

You may like

-

Exploring Day Trips From Lehi Through Scripture

-

Lehi nostalgic Christmas gifts for sale at Historical Society

-

Lehi wrestlers win at Stansbury

-

Lehi firefighters help Santa

-

Lehi-based App Encourages: Get fit with friends

-

ASD plans to adopt Lacrosse for 2020-21 school year

-

Remodels revive community spirit

-

Family Night at Hutchings Museum a hit with families

-

Fastpitch Softball—It’s all in the (Lehi) family

-

Lehi donors recognized at ASD Foundation event